Can Human Females Form a Prostate?

Laurence Baskin, MD1, Mei Cao, MD1, Adriane Sinclair, PhD1, Chad Vezina, PhD2, Simon Hayward, PhD3, Gerald Cunha, PhD1.

1UCSF, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA, 3University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Background: An XX karyotype is destined to form the female phenotype except in the rare patient with severe congenital adrenal hyperplasia and or patients exposed in utero to androgens. The hypothesis to be tested, can human females form a prostate?

Methods: The ontogeny of the human fetal prostate (N=26) from 7-21 weeks gestation was defined by morphology, histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC) for key markers of prostatic development. Xenografts of human fetal prostates (11-14 weeks gestation) were grafted into castrated male athymic mice that were either untreated (N=4) or treated with dihydrotestosterone (DHT) (N=4) via subcutaneous pellet (20 mg). Grafts were harvested at 4-8 weeks. These were compared to the segment of the human fetal proximal female urethra immediately below the bladder also grafted into castrated DHT-treated hosts (N=8) and control hosts (N=4).

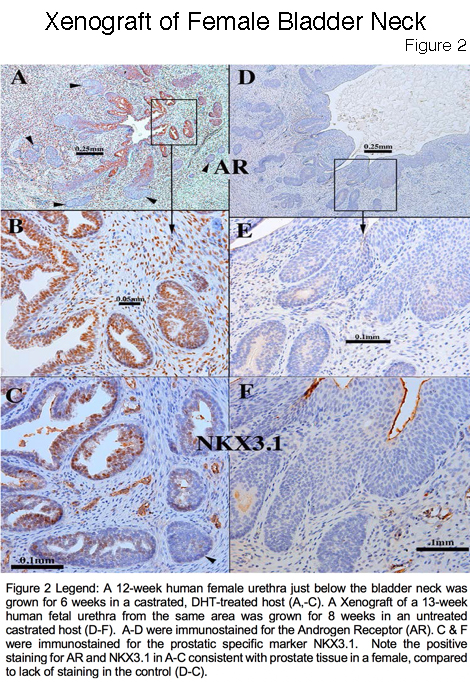

Results: The human fetal prostate undergoes five unique stages of differentiation: (a) pre-bud, (b) emergence of solid prostatic epithelial buds from urogenital sinus epithelium, (c) bud elongation and branching, (d) canalization of the solid "ducts", (e) differentiation of luminal and basal epithelial cells, and (f) secretory cytodifferentiation (Figure 1). Both the male and female (Figure 2 A-C) xenografts exposure to DHT contained an abundance of prostate-like solid epithelial cords and canalized ducts. The typical range of prostatic epithelial markers was observed: Cytokeratin 7, 8, 19, TP63, the androgen receptor (AR), NKX3.1(prostate specific epithelial marker) (Figure 2C), and the definitive prostate secretary proteins PSA and PAP (Figure 3). This was in contrast to the male and female xenografts grown in the castrate male host that exhibited solid and immature cords and lack of expression of AR, NKX3.1, PSA and PAP (Figure 2 D-F). In addition, the control xenografts of human fetal female urethra maintained a urethra-like structure with associated solid epithelial buds.

Conclusion: Prostatic differentiation was induced by DHT in human fetal female urethral xenografts and was absent in androgen-deficient control xenografts. The fact that prostatic tissue can form in females (exposed to androgens) may have clinical implications for patients with disorders of sex development such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia and transgender patients.

Back to 2019 Abstracts