End-stage and chronic kidney disease in classic bladder exstrophy

Joshua D. Roth, MD, PhD1, Diana K. Bowen, MD2, Molly E. Fuchs, MD3, Patricio C. Gargollo, MD4, Harrison C. Gottlich, BA4, David S. Hains, MD1, Andrew Strine, MD, MPH5, Konrad M. Szymanski, MD, MPH1.

1Riley Children's Health at Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2Lurie Children's Hospital, Chicago, IL, USA, 3Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA, 4Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA, 5Cincinnati Children's Hospital, Cincinnati, OH, USA. End-stage and chronic kidney disease in classic bladder exstrophy

Joshua D. Roth MD PhD, Diana K. Bowen MD, Molly E. Fuchs MD, Patricio C. Gargollo MD, Harrison Gottlich, David S. Hains MD, Andrew Strine MD MPH, Konrad M. Szymanski MD MPH

Introduction: While most children with classic bladder exstrophy (CBE) are born with normal kidneys, some experience renal deterioration in adulthood. Little is known about the incidence of end-stage and chronic kidney disease (ESKD and CKD, respectively) in this population. Our group has recently published on surgical outcomes of a multi-institutional cohort of 216 people with CBE. Our aim was to describe the incidence of ESKD and prevalence CKD in this cohort of people with CBE.

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed records of patients with CBE followed at five tertiary care centers described previously. The primary outcome was incidence of ESKD, defined as permanent peritoneal/hemodialysis or renal transplantation. The secondary outcome was prevalence of CKD stage 3 or higher (CKD3+, estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR]<60ml/min/1.73m2) at the last appointment. Creatinine-based eGFRs were calculated using the CKD-EPI Creatinine Equation (adults) and the Schwartz formula (children). Survival analysis and Fisher’s exact test were used.

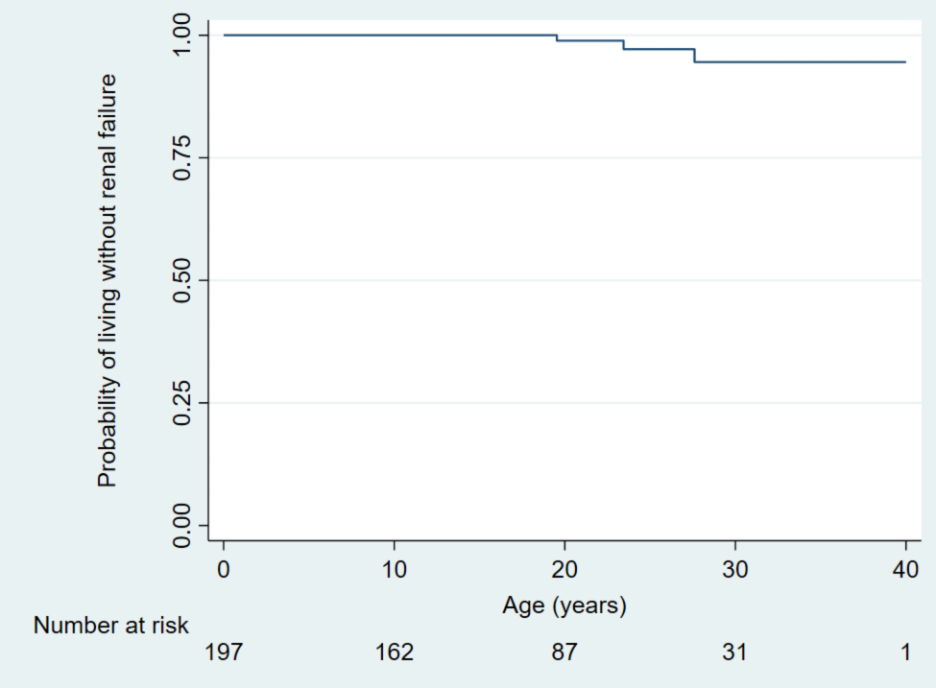

Results: A total of 201 patients (93% of the original cohort) had renal function data available (63% male). Four patients who had a primary urinary diversion remained diverted at a median follow-up of 20.1 years old. None developed ESKD and one developed CKD3+. Remaining 197 patients had a primary bladder closure. At a median follow-up of 18.8 years old, 12 were diverted, 108 were augmented and 77 were neither. Three patients developed ESKD (1.5%) at a median age of 23.4 years (1 hemodialysis, 2 transplantation). On survival analysis, the risk of ESKD was 0% at 10 years, 1% at 20 years and 5% at 30 years (Figure). This was higher than the risk of 0.003% at 21-year-olds in the general population (p<0.001). Median age of 147 individuals with eGFR data was 20.5 years old (65% male). One child (2%) and 8 adults (8%) had CKD3+ (p=0.16). On exploratory analyses, prevalence of CKD3+ did not differ by center (p=0.80) or birth year among 95 adults (p=0.99).

Conclusions: The risk of ESKD among patients with CBE is not insignificant and appears to be more common than the general population. The potential role of modifiable contributing factors, such as increased bladder outlet resistance, warrants further investigation. Reliable long term follow up is needed in this population to monitor for ESKD.

Figure. End-stage kidney disease among people with classic bladder exstrophy after primary bladder closure.

Back to 2023 Abstracts